The Economics of Makeshifts

While some makeshifts provide temporary relief, they often perpetuate cycles of poverty rather than offering a path to upward mobility

I buy groceries; sukuma wiki, tomatoes, onions, garlic, from women and men stationed beside roadsides. Our byzantine economy runs on the veins of the laboring women and men who occupy an unfamiliar role of shouldering society together at the seams and fixing it when things fall apart.

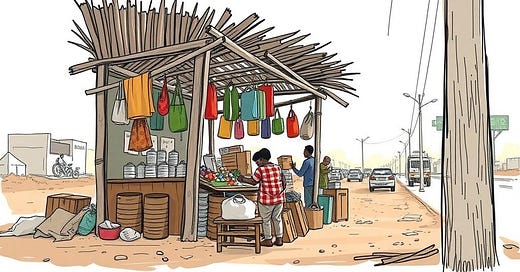

Today, in the midst of economic civilization, nothing much has changed. Even with the swapping of economic templates, signs of a throbbing economy still teeteers on loose threads. A cursory look over the urban reveals the not uncommon trend; makeshifts cascading through busy street lanes— sun hitting on them mercilessly and raindrops pattering on their scarecrow-like temporary structures. A widow, a disabled, a young boy; all in a desparate mode to squeeze a shilling out of the barren street. This is the economy of makeshifts'—a patchwork system of survival circumventing a rather rigid formal economic structures.

But, what might be seen straight-forwardly as mere makeshifts by the authorities, might by the user, be viewed as solutions to poverty, dearth, crisis, under-and unemployment.

The economy of makeshifts mushrooms where formal structures fail. It’s visible in the crowded lanes of urban markets, where makeshift stalls lay dense like refugee camps. It’s in the women who sell sukuma wiki and tomatoes on street corners, sustaining families with the little they earn. It’s in the underpaid workers who fill the gaps in our economy, keeping costs low for everyone but themselves. It is, in essence, the struggle of those who hold society together when everything else crumbles.

The idea of makeshift economies stretches to the early modern Europe. Social historians have documented how the poor relied on a combination of state relief, religious charity, kinship networks, and petty trade to make ends meet. The industrial revolution, while increasing overall wealth, widened economic disparities, forcing a significant number to turn to creative low-grade grind.

Women often took in laundry or mended clothes to earn extra income. Children worked as street sellers or apprentices in unregulated trades. Begging was both a necessity and an art, with individuals crafting compelling narratives to elicit alms. Some engaged in illicit activities—smuggling, theft, and fraud—while others benefited from institutional support through almshouses or parish relief.

Women, in particular, bear the brunt, accepting low wages, enduring unsafe conditions, and working without protections like paid leave or retirement benefits.

The gender property gap tells the same story: while 0.5% of men aged 15–19 own land, women in the same bracket own nothing. By middle age, men’s ownership rises to 11.6%, leaving women far behind. In the SME sector, unlicensed businesses—often women-led—account for 61%, laying bare the survival-driven makeshift economy that regulatory systems fail to accommodate.

Critics argue that the economy of makeshifts romanticizes poverty, adding that the poor are resourceful rather than victims of structural inequality. This is not far from the truth, but this perspective overlooks the coercive nature of such survival strategies. Many are forced into dangerous, exploitative, or illegal work due to the absence of viable alternatives. While some makeshifts provide temporary relief, they often perpetuate cycles of poverty rather than offering a path to upward mobility.

The worst thing to be said is people struggling on the margins have no real freedom. Without security, they cannot escape poverty’s firm grip. The economy of makeshifts is yet to remain a historical fact—it still persists in today’s gig economy, informal labor markets, and grassroots survival strategies in developing nations. Understanding how past societies managed economic insecurity can inform modern social policies, ensuring that makeshift survival does not become a necessity but a choice.